Eulalia of Mérida

Until today Eulalia of Mérida is one of the best known and most venerated martyrs in Spain. The origins of her veneration, however, can already be found in late antiquity, where her account joins those of other strong women.

The details of this martyr story should be familiar to our regular readers by now; as the others Eulalia was a young girl from a good family, distinguished by a particularly outstanding modesty, chastity and piety. Like the two previous women, she criticized the worship of pagan idols and overturned one to make her point. Similar to Salsa of Tipasa, she was later venerated as the patron saint of her hometown; as in the case of Marciana of Caesarea, two cities invoke her martyrdom. Thus there is an Eulalia of Mérida and one of Barcelona whose stories are so similar that it cannot possibly be a coincidence …

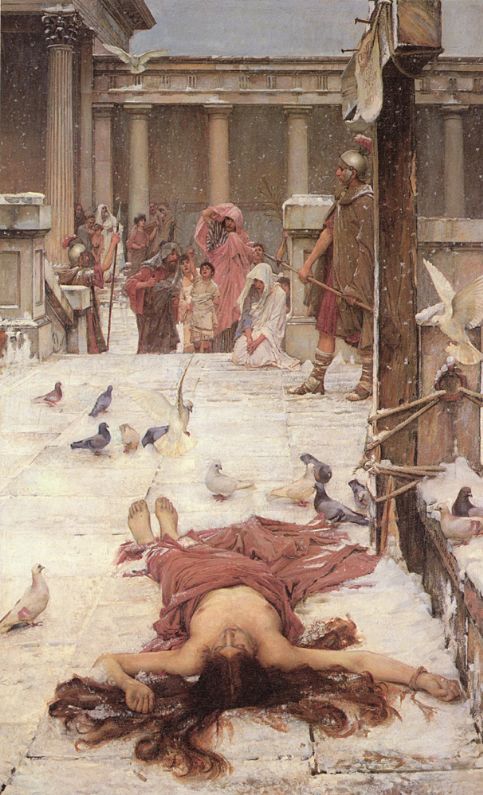

The martyrdom of Eulalia was handed down by Prudentius in the 3rd hymn of his Peristephanon. The Iberian poet describes the young Eulalia as the daughter of a wealthy family who had been instructed in the Christian faith by her mother. In the course of the persecution of Christians in 304 CE under the Roman Emperor Diocletian, the young girl, inspired by the steadfastness of other Christians, wanted to stand up for her Christian faith as well. For this reason, she sneaked out of her parents' house at night to confront the Roman governor in Augusta Emerita (mod. Mérida), the capital of the province of Lusitania and part of the dioecesis Hispaniarum. Courageously, she stood before him and publicly professed her Christian faith - more than that, she did not hesitate to explain to the governor and the crowd present that in the pagan idols they were merely worshipping man-made objects. Finally, she spat in the governor's face and knocked over the statue present. As a result, she was then captured and sentenced first to torture and later to death at the pyre. Among other things, the girl, who was only twelve years old, was splashed with hot oil and thrown into a furnace, but miraculously her body remained unharmed. In this way, this is similar to the portrayal of other women. They are indeed threatened with violence, in the case of Marciana of Caesarea, for example, in the form of rape, but in many cases they are miraculously protected, so that there is no description of the effects of these uses of violence on the bodies of the martyrs. After being unsuccessfully tortured, she was taken to a funeral pyre and set on fire. In the process, the liberated soul of the martyr disappeared from her body in form of a white dove - a Christian symbol already popular in late antiquity - and snow covered the corpse like a veil.

Her relics were later buried and a church built over them, which became the focus of the martyr's veneration. The main actors were now the local bishops of Mérida, who controlled their representation and veneration. In this sense, Saint Eulalia became the adornment of the city and even protected it from plundering; first by the Suebi and later a second time by the Visigoth Theoderic II. The cult of Eulalia quickly spread beyond the borders of the Iberian Peninsula, and even the church father Augustine of Hippo dedicated a sermon to the holy virgin. In addition, the image of the young girl can be found in the martyr's procession in S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna from the 6th century and her relics have even reached today's Warsaw. The impressive story of the martyr gives an idea of why she became so popular so quickly. One question that remains unanswered, however, is where the real Saint Eulalia is located - in Mérida at her origins or maybe in Barcelona, or is her modern image composed of all the pieces of the mosaic of her veneration?

Nathalie Klinck, M.A. (Universität Hamburg)